How Ukraine Views Its Relations With China

China’s ever-closer ties with Russia have led to a marked deterioration in its engagement with Ukraine.

By Vita Golod and Dmytro Yefremov

The source: https://thediplomat.com/2025/09/how-ukraine-views-its-relations-with-china

Ukraine’s ties with China remain anchored in a symbolic legacy: the $1.5 billion loan agreement signed in 2013 between the State Food and Grain Corporation of Ukraine and China’s Export-Import Bank. Just recently, Kyiv reaffirmed its state guarantee on the debt, under renegotiated terms that postpone repayment of both principal and interest. The move, signed by newly appointed Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko, was less about economics than about signaling a willingness to preserve what little remains of high-level contact with Beijing.

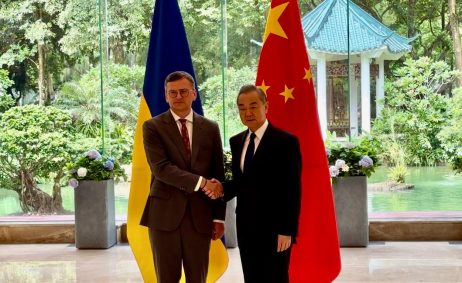

Yet beyond this gesture, the relationship is stagnant. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and China’s top leader Xi Jinping have spoken only once, and interactions among officials, diplomats, and intellectual circles have largely dried up. Beijing’s disinterest was underscored this month, when Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited neighboring Poland but pointedly skipped neighboring Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Wang’s visit to Warsaw included high-level talks with Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski and President Karol Nawrocki. The omission of Ukraine underscored Beijing’s careful need to maintain dialogue with EU states like Poland while avoiding moves that might be read as distancing itself from Moscow.

In Kyiv, Poland’s experience in dealing with China is being studied closely. Both countries have signed a memorandum on the Belt and Road Initiative, yet Warsaw has reaped far greater benefits, securing tangible results well before the EU adopted its broader “de-risking” approach. But Wang’s visit showed that Poland and China remain fundamentally out of sync on strategic questions, with Warsaw emphasizing security and accountability in response to Russia’s war while Beijing avoids naming Moscow and maintains its posture as a neutral mediator.

Despite the political distance, China remains Ukraine’s largest trading partner. In 2024, bilateral trade reached $16.8 billion, heavily tilted in Beijing’s favor. Imports dominated – most notably $1.1 billion in drones and components for Ukraine’s army – while Ukrainian exports totaled just $2.4 billion, largely grain, sunflower oil, and iron ore.

Ironically, Ukraine’s Export Strategy 2030, announced in March 2025, assigns only a marginal role to China. Instead, it prioritizes alignment with the European Union and seeks to reduce the share of raw materials in exports to 59 percent, shifting toward higher value-added goods. While this transformation could, in theory, provide opportunities for Chinese firms to localize production in Ukraine, it has not yet materialized. Instead, European companies have already demonstrated strong readiness to move into this space with financing support – leaving limited room for Chinese investment.

Politically, the picture is far bleaker. China’s ever-closer ties with Russia have led to a marked deterioration in its engagement with Ukraine. Beijing has repeatedly defended this relationship, insisting that “normal cooperation between Chinese and Russian companies complies with WTO rules and market principles; it is not directed against third parties and should not be obstructed.”

Since the outset of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Beijing has drastically scaled back bilateral political dialogue with Ukraine, signaling its perception of Kyiv as lacking autonomous strategic weight. In stark contrast, China’s coordination with Moscow has become more systematic and frequent – developments that Kyiv views as direct security threats. Only in 2024, after Beijing effectively undermined Ukraine’s peace initiatives, did Zelenskyy shift toward a more pragmatic and instrumental approach to dealing with China, coupling it with sharper public criticism of Beijing. This adjustment was also shaped by broader geopolitical disarray following Donald Trump’s return to the U.S. presidency and the onset of a more isolationist U.S. foreign policy.

Despite this political chill, China has remained active in Ukraine’s economic landscape. Chinese Ambassador to Ukraine Ma Shengkun has sought to keep business channels open, promoting access for Ukrainian peas and aquaculture products to the Chinese market. The Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce has become the main venue for hosting Chinese delegations, which increasingly promote electric vehicles and consumer goods while exploring participation in postwar reconstruction. With ceasefire talks gaining momentum, the number of Chinese visits has grown significantly. Yet these have been limited to small- and medium-scale missions, not the large flagship projects once associated with the Belt and Road Initiative.

For Ukraine’s agrarian sector, China remains a priority market. A 2025 AgroPolit survey showed that 40 percent of respondents continue to identify China as critical for agricultural exports. Beijing could capitalize on this enduring interest by expanding access for Ukrainian products, as it has done for ASEAN countries. Yet access to the Chinese market has increasingly become politicized. Protocols for poultry and other goods have been blocked, and every instance of Ukrainian criticism of China has brought direct consequences for trade negotiations. In this sense, Beijing’s commercial leverage is viewed in Kyiv as a tool of geopolitical pressure, not as neutral economic cooperation.

Beyond the economic sphere, Ambassador Ma recently published an article in Interfax-Ukraine promoting China’s Global Governance Initiative, a concept launched by Xi Jinping at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Tianjin. The initiative, now a Chinese Communist Party priority, emphasizes sovereign equality, international law, multilateralism, and a human-centered approach, and policy effectiveness.

In Ukraine, China’s diplomatic messaging appears insincere, given the realities of the war and Beijing’s stance on it; it is seen less as neutral mediation than as an effort to shield Moscow from defeat or regime change. Abstract commitments and soft power strategies carry little weight as Beijing has failed to engage meaningfully with Ukraine’s public opinion and civil society, beyond elite diplomacy or economic deals.

Public opinion data reinforces this view. A survey conducted by Active Group jointly with Experts Club in August showed that 40.7 percent of Ukrainians have a negative view of China (30 percent mostly negative, 10.7 percent completely negative). Respondents cited China’s ambiguous foreign policy and perceived bias toward Russia as their primary concerns. There is widespread distrust of Beijing’s efforts to position itself as an international peace mediator. This skepticism constrains the Ukrainian leadership’s room for maneuver: any overtures toward China risk being seen domestically as accommodation to a state perceived as unfriendly, if not hostile.

Against this backdrop, Ukraine’s overriding priority remains national survival. Its integration with the European Union is best understood as a means to that end. This trajectory ensures that Kyiv will increasingly adopt EU standards and norms, including a gradual alignment of its approach to China with the broader European consensus. Across Europe, China’s assertive economic behavior has shifted the prevailing logic from cooperation to security-driven caution.

Future cooperation between Ukraine and China will remain possible – and, in some cases, even strategically desirable. Given recent restrictions on Ukrainian agricultural exports to the EU, China could serve as an outlet for surplus agri-exports, relieving pressure on European markets. Yet the challenge for Ukraine will be to develop this trade while avoiding excessive dependence on Beijing, which has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to wield commerce as a political weapon.

Over the longer term, Ukraine’s Export Strategy 2030 reinforces this trajectory: by anchoring itself in the EU’s collective trade approach toward China, Kyiv hopes to safeguard its economic interests within the broader umbrella of European security and regulatory norms.