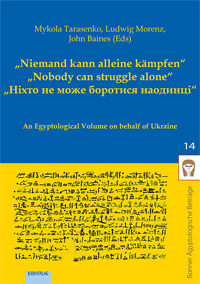

“Niemand kann alleine kämpfen” “Nobody can struggle alone” “Ніхто не може боротися наодинці”: an Egyptological volume on behalf of Ukraine

The war of Russia against Ukraine is also a war against a culture, and for this reason it affects even a small subject like Egyptology. Twenty-four authors from eight countries have come together to contribute to a volume that intends to display our solidarity with Ukraine and to make plain that all of us seek actively to sustain cultures – in our case the understanding of that of the Nile with its more than three millennia of history – through engagement and shared conversations. By means of this joint undertaking we wish to counter brute force with the self-evident necessity of cultural exchange, both in our field of study and beyond.

M. Tarasenko, L. Morenz, J. Baines (ed.) “Niemand kann alleine kämpfen” “Nobody can struggle alone” “Ніхто не може боротися наодинці”: an Egyptological volume on behalf of Ukraine. Bonner Ägyptologische Beiträge. Bd. 14. Berlin. 2024

ISBN-10 386893443X

ISBN-13 978-3868934434

What Trump’s Tilt Toward Russia Means for China.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s negotiations with Russia are not only occurring at Ukraine’s expense but also carry broader implications for China. Historically, the opposite was true – Henry Kissinger’s strategic opening to China contributed to the Soviet Union’s eventual collapse. Now, the Trump administration is playing a calculated game with Russia, aiming to secure economic benefits such as cheaper raw materials while attempting to reshape Sino-Russian relations. The goal appears to be to pull Moscow away from Beijing and weaken their growing alignment.

However, a repeat of the Sino-Russian split seems unlikely in today’s geopolitical landscape, as both Russia and China remain skeptical of Trump’s erratic foreign policy and question the reliability of U.S. commitments.

Trump’s confrontational stance toward Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been a political shock for both Ukraine and Europe. Notably, the Trump administration, whether intentionally or not, has adopted China’s rhetoric over the past three years, referring to the Russia-Ukraine War merely as a “conflict” and promoting peace through negotiations with Russia. This approach was first put forward by China in February 2023 and has since been aggressively pushed through state-controlled media and diplomatic channels, including special envoy Li Hui. Now the Trump administration has repackaged this strategy in a more unilateral manner, with a key difference – amid Russia-U.S. talks, Ukraine and Europe are largely excluded from the decision-making process. The fate of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity is being discussed behind closed doors, without its participation.

Paul of Aleppo’s Journal. Vol. 1. Syria, Constantinople, Moldavia, Wallachia and the Cossaks’ Lands

Paul of Aleppo’s Journal. Vol. 1. Syria, Constantinople, Moldavia, Wallachia and the Cossaks’ Lands / Introductory Study, Arabic Edition and English Translation by Ioana Feodorov with Yulia Petrova, Mihai Țipău and Samuel Noble. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2024. 897 p.

https://brill.com/display/title/70121

Paul of Aleppo, an archdeacon of the Church of Antioch, journeyed with his father Patriarch Makarios III ibn al-Za’im to Constantinople, Moldavia, Wallachia and the Cossack’s lands in 1652-1654, before heading for Moscow. This book presents his travel notes, preceded by his record of the patriarchs of the Church of Antioch and the story of his father’s office as a bishop and election to the patriarchal seat. The author gives detailed information on the contemporary events in Ottoman Syria and provides rich and diverse information on the history, culture, and religious life of all the lands he travelled across.

ISSN 2468-2454

ISBN 978-90-04-69633-4 (hardback)

ISBN 978-90-04-69682-2 (e-book)

The academic journal “The World of the Orient” entered the 1st quartile of the Scopus

The academic journal “The World of the Orient” entered the 1st quartile of the Scopus international scientometric database in religious studies area. We remind you that “The World of the Orient” has been indexed in the Scopus database since 2019 in the following specialties: history, linguistics, philosophy,religious studies.In three other specialties, “The World of the Orient” entered the 2ndquartile of Scopus (according to SCImago Journal & Country Rank). The journal aims to activate academic research in the fieldofOriental Studies in Ukraine, to assert Oriental Studies as an important and integral part of Ukrainian humanitarian knowledge. The journal’s objectives are to promote the development of Oriental Studies, to introduce new sources into scientific circulation, to popularize the latest scientific achievements, to raise the level of research and to develop comprehensive scientific cooperation in this field. Since 1993, authors from more than 25 countries have published in the journal.

30.11.23 ХХVI A. Krymskyi Annual Memorial Conference on Oriental Studies

Dear colleagues!

We kindly invite you to take part in the International scientific conference “ХХVI A. Krymskyi Annual Memorial Conference on Oriental Studies”.

The conference will be held on November 30, 2023.

04.05.2022 The Third International Round Table “Pre-Islamic Near East: History, Religion, Culture”.

Dear colleagues,

We invite you to take part in the Third International Scientific Round Table “Pre-Islamic Near East: History, Religion, Culture”, which will be held on May 04, 2022.

On September 27, 1822, the French Orientalist Jean-François Champollion at a meeting of the Academy of Inscriptions in Paris announced his well-known “Letter to Mr. Docier on the alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphs” (Lettre à Mr. Dacier relative à l’alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques) about his discovery of a method for decryption of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. This event marked the appearance of a new discipline in Oriental studies – Egyptology. The Organizing Committee decided to time this year`s round table to the 200th Anniversary of Egyptology.

Historians, archaeologists, specialists in the history of religion, and philologists specializing in the study of ancient cultures of the Near East region are invited to participate in the meeting.

Working languages: Ukrainian, English.

Report schedule: up to 20 minutes.

Organizational fee is not provided.

The round table is planned to be held in a mixed format (face-to-face participation and zoom-conference mode).

Please confirm your participation in the meeting and send the topic and abstracts of the report by March 20, 2022 to the following e-mail addresses: niktarasenko@ukr.net; myktarasenko@gmail.com

Chairman of Organizing Committee: Mykola Tarasenko.

Secretary of Organizing Committee: Hanna Vertiienko.

It is planned to publish Abstracts and a Collection of Materials.

Requirements for the application and abstracts:

Title of the report, surname and name of the authors, e-mail address, academic degree, institution, city where the institution is located, country, text of abstracts (approx. 2000 characters with spaces) in Ukrainian and English languages).

Call for Papers 2022 (print version)

Liudmyla Kucheria

Usenko IMAGES OF ANCIENT EGYPT IN MODERN MASS CULTURE (ON THE EXAMPLE OF THE FILM “GODS OF EGYPT”)

IMAGES OF ANCIENT EGYPT IN MODERN MASS CULTURE (ON THE EXAMPLE OF THE FILM “GODS OF EGYPT”)

I. V. Usenko

Student V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University 4, Svobody Sq., Kharkiv, 61022, Ukraine usenkingo@gmail.com

This article with the help of semiotic and hermeneutic methods highlights the representation of Ancient Egypt images in mass modern culture on the example of the film “Gods of Egypt”. Nowadays the interest in ancient Egyptian art culture and history is presented not only in scientific perspective but also in mass culture. Each of these works includes a unique vision and interpretation of myths and history created by the author. However not all of them include representation of history and culture of Egypt that may be called authentic. This work with the help of analysis depicts the way of interpretation of mythological material in the film, namely the interpretation of Osiris myth, myths about the Solar vessel and the afterlife. The images of Egyptian gods are examined and compared with their representation in the film, particularly it is made with the help of colour symbolism in Egyptian culture. It also turns out, that film as a product of modern mass media includes techniques, that belong to mass culture such as citation technique (depiction of Sauron’s tower – Barad Dur from the thrilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien, filmed by the director Peter Jackson), standardization, usage of basic plots (conflict between good and evil). Mass culture is a phenomenon which is based on the generalization and availability, but in many cases it leads to simplification that violates the logic of authentic meanings. Therefore, despite the fact that “Gods of Egypt” include the reflection of Egyptian culture and mythology, the analysis showed that the film lost its authenticity and logic of perception (binary that is represented in the ancient Egyptian culture by terms “Isfet and Maat”) due to standardization. Also the accent in the film was made on the conflict between good and evil, presented by figures of Seth and Horus.

Keywords: mass modern culture, “The Gods of Egypt”, Osirian Myth, Osiris, Egyptian culture, Egyptian mythology

Preislamic Near East 2021, (2):181-187

https://doi.org/10.15407/preislamic2021.02.181

Full text (PDF)

REFERENCES

Karlova K. F. (2018), “Set – Vladyka Isefet: k voprosu ob interpretatsii epiteta”, Vestnik Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo oblastnogo universiteta. Seriya: Istoriya I politicheskiye nauki, No. 3. pp. 40–7. (In Russian).

Karlova K. F. (2020), “Peribsen i Nizhniy Egipet”, Oriyentalistika, Vol. 3, No. 5, pp. 1249–58. (In Russian). https://doi.org/10.31696/2618-7043-2020-3-5-1249-1258

Lavrentyeva N. V. (2012), Mir ushedshikh. Duat: obraz inogo mira v iskusstve Egipta (Drevneye i Sredneye Tsarstva), Russkiy fond sodeystviya obrazovaniyu i nauke, Moscow. (In Russian).

Lipinskaya Y. and Martsinyak M. (1983), Mifologiya Drevnego Egipta, translated by E. Gessen, Iskusstvo, Moscow. (In Russian).

Plutarkh (1996), Isida i Osiris, translated by N. Trukhina, UTSIMM-PRESS, Kiev. (In Russian).

Rak. I. V. (2004), Egipetskaya mifologiya, Knizhnyy klub, Kharkov. (In Russian).

Zhdanov V. V. (2006), Evolyutsiya kategorii Maat v drevneyegipetskoy mysli, Sovremennyye tetrad, Moscow. (In Russian).

Assmann J. (2005), Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt, translated by D. Lorton, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

Boddy-Evans A. (2019), “Colors of Ancient Egypt”, available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/colors-of-ancient-egypt-43718 (accessed: 20.02.2020).

Bogg J. (2007), “Ancient Egyptian Royalty”, available at: http://djeserkara-royalty.blogspot.com/ (accessed: 20.02.2020).

Smith M. (2017), Following Osiris, Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2753906700002205

Tarasenko SERHIY DONICH (1900–1958): THE FATE OF EGYPTOLOGIST IN SOVIET UKRAINE

SERHIY DONICH (1900–1958): THE FATE OF EGYPTOLOGIST IN SOVIET UKRAINE

M. O. Tarasenko

DSc (History) A. Yu. Krymskyi Institute of Oriental Studies, NAS of Ukraine 4, Hrushevskoho Str., Kyiv, 01001, Ukraine niktarasenko@yahoo.com

In 2020, it was 120 years anniversary of Serhiy Donich, the only Egyptologist in Soviet Ukraine in the second quarter of the 20th century. He was born in 1900 at Dzegam of Yelisavetgrad province (Tavluz district, Azerbaijan). In 1921 he entered the University of Kamyanets-Podilsky and at the same time worked at the astronomical Observatory. In the summer of 1923 he moved to Odessa. Here, working at the Odessa University Observatory, he began to study Oriental and African languages, and Egyptology became the main subject of his interest. The second half of the 1920s and 1930s was the time of his most productive research activity. At this time he established contacts with other Soviet and Western Egyptologists. In 1929 he became a member of the Egyptological Section at Leningrad University and underwent an internship at the State Hermitage Museum. From 1927 to 1945 Donich worked as the head of the Department of “Ancient Egypt” at the Odessa Historical and Archaeological Museum (Odessa Archaeological Museum now). During this time he processed the Egyptian collection, made its inventory and created a card catalog of identifications of more than 600 artifacts, created the new exhibitions, conducted tours, participated in archaeological expeditions, published articles in three languages in Odessa, Moscow, and Leningrad. With the beginning of World War II, Donich was drafted to the Red Army in 1941, but was taken prisoner soon, escaped, and returned to Odessa, where he returned to work at the museum. In 1945, S. Donich was arrested and unjustifiably sentenced to 10 years for allegedly assisting the Romanian administration in removing cultural property from the Historical and Archaeological Museum. His criminal case was soon reconsidered, and in 1946 he was released under an amnesty. Later, the scholar worked in a number of Odessa libraries, and in the last years of his life he returned to work at the Observatory. After a long break, in 1958 his Egyptological article was published in Moscow, which gave hope for the resumption of research activity, but at that time the scholar was already terminally ill. He died on December 26, 1958. Serhiy Donich was rehabilitated in 1997.

Keywords: Serhiy V. Donich, Odessa, Egyptology, Oriental Studies, Odessa Archaeological Museum, Soviet Period

Preislamic Near East 2021, (2):147-180

https://doi.org/10.15407/preislamic2021.02.147

Full text (PDF)

REFERENCES

Alenich A. A. and Donich S. V. (1923), “Mayskiye Akvaridy v 1921 g.”, Mirovedeniye. Izvestiya russkogo obshchestva lyubiteley mirovedeniya, T. XII, April, no. 1 (44), pp. 44–6. (In Russian).

Arutyunova I. V. and Pikanovskaya L. V. (2020), Spisok pamyatnikov istorii (mogil) na 2-m gorodskom kladbishche. Chast’ 2-ya, Konfetka, Odessa. (In Russian).

Balasohlo V. B. and Donich S. V. (1937), “Sposterezhennya sonyachnykh plyam na heliohrafi Odes’koyi observatoriyi”, Trudy Odes’koho Derzhavnoho Universytetu. Zbirnyk astronomichnoyi Observatoriyi, T. II, Odesa, pp. 63–8. (In Ukrainian).

Bolshakov A. O. (2011), “Leningradskiy Egiptologicheskiy kruzhok: u istokov sovetskoy egiptologii”, in L. I. Dryomova (ed.), Kul’turno-antropologicheskiye issledovaniya, Vol. 2, NGPU, Novosibirsk, pp. 5–10. (In Russian).

Bochkareva A. S. (2010), “Formirovaniye agitatsionno-propagandistskikh organov i uchrezhdeniy v Sovetskoy Rossii (1920-e gody)”, Kul’turnaya zhizn’ Yuga Rossii, No. 4 (38), pp. 44–7. (In Russian).

Donich S. V. (1930), “Dodatky do opysu musul’mans’kykh pam’yatnykiv M. Spafarysa, shcho v XXXII tomi ‘Zapisok Odesskogo Obshchestva Istorii y Drevnostey’ ”, Visnyk Odes’koyi komisiyi krayeznavstva, Sektsiya arkheolohichna, Nos. 4–5, pp. 60–61. (In Ukrainian).

Donich S. V. (1930a), “Try ehypets’ki konusy Odes’koho Derzhavnoho Istrychno-Arkheolohichnoho Muzeyu”, Visnyk Odes’koyi komisiyi krayeznavstva, Sektsiya arkheolohichna, Nos. 4–5, pp. 59, 62–3. (In Ukrainian).

Donič S. V. (1958), “O zvukovom potentsiale dvukh egipetskikh grafem”, Sovetskoye vostokovedeniye, No. 6, pp. 85–8. (In Russian).

Kolesnichenko A. N. and Polishchuk L. Yu. (2016), “Odesskiy arkheologicheskiy muzey v period okkupatsii: neskol’ko stranits istorii”, Visnyk Odes’koho istoryko-krayeznavchoho muzeyu, Vol. 15, pp. 228–32. (In Russian).

Levchenko V. V. (2006), “Zhyttya ta naukovo-hromads’ka diyal’nist’ Valentyna Ivanovycha Selinova (do 130-richchya z dnya narodzhennya)”, Yugo-Zapad. Odessika. Istoriko-krayevedcheskiy nauchnyy al’manakh, Vol. 2, pp. 256–66. (In Ukrainian).

Levchenko V. V. (2016), “Istoriograficheskaya nakhodka: otzyv professora A. G. Gotalova-Gotliba o doktorskoy dissertatsii professora V. I. Selinova”, Pіvdenniy zakhіd. Odesika. Іstoriko-kraєznavchiy naukoviy al’manakh, Vol. 21, pp. 168–90. (In Russian).

Levchenko V. (2018), “Rol’ odes’kykh vchenykh-istorykiv u doslidzhenni, okhoroni ta zberezhenni Ol’viyi u pershiy polovyni KhKh stolittya”, Krayeznavstvo, No. 1 (102), pp. 143–60. (In Ukrianian).

Odes’kyy arkheolohichnyy muzey. Korotkyy putivnyk (1959), OAM, Odesa. (In Ukrainian).

Smirnov V. (2003), Rekviyem XX veka. V pyati chastyakh. Part II, Astroprint, Odessa.

Smirnov V. (2007), Rekviyem XX veka. V pyati chastyakh. Part IV, Astroprint, Odessa.

Smirnov V. (2013), Rekviyem XX veka. V pyati chastyakh. Part II, 2nd Ed., Astroprint, Odessa.

Tarasenko N. A. (2018), “Fragmenty drevneegypetskoy Knigi mertvykh v Ukraine”, Starodavnye Prychornomor’ya, Vol. XII, pp. 517–24. (In Russian).

Tarasenko M. O. (2020), “Serhiy Volodymyrovych Donich: 120 rokiv vid dnya narodzhennya”, Shodoznavstvo, No. 86, pp. 181–4. (In Ukrainian). https://doi.org/10.15407/skhodoznavstvo2020.86.181

Tarasenko M. O. and Hereikhanova D. K. (2020), “Neopublikovana stattya S. V. Donicha ‘Zhertovnyk Isidy. Inv. 51843 Odes’koho istorychnoho muzeya’ (RA NF OAM № 59405)”, Shodoznavstvo, No. 86, pp. 139–62. (In Ukrainian). https://doi.org/10.15407/skhodoznavstvo2020.86.139

Ursu D. (1994), “Z istoriyi skhodoznavstva na Pivdni Ukrayiny”, Shìdnij svìt, Nos. 1–2, pp. 135–50. (In Ukrainian).

Ursu D. P. and Levchenko V. V. (2009), “Donich Serhiy Volodymyrovych, 1900–1958”, Odes’ki istoryky. Entsyklopedychne vydannya, Vol. I (pochatok XIX – seredyna XX st.), Drukars’kyy dim, Odesa. (In Ukrainian).

Shtaude N. M. (1923), “A. A. Alenich. Nekrolog”, Mirovedeniye. Izvestiya russkogo obshchestva lyubiteley mirovedeniya, T. XII, no. 2 (45), pp. 224–8. (In Russian).

Yushmanov N. V. (1928), Grammatika literaturnogo arabskogo yazyka; ed. and Preface by I. Yu. Krachkovskogo, Izd-vo Leningryu Vost. Inst-ta. im Enukidze, Leningrad, 1928. (In Russian).

Bierbrier M. L. (2012), Who was who in Egyptology, 4th Ed., Egypt Exploration Society, London.

Albright W. F. (1918), “Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology”, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1086/369848

Albright W. F. (1918a), “Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology, II”, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 215–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/369866

Albright W. F. (1927), “Notes on Egypto-Semitic Etymology, III”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 47, pp. 198–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/593260

Donič S. (1929), “The Sarcophagus of Ptahthru, № 3 of the History and Archaeology Museum of Odessa”, Doklady akademii nauk SSSR, Ser. V, no. 8, pp. 149–51.

Donitсh S. (1930), “Funeral cones of the Odessa Archeological Museum”, Sbornik egiptologicheskogo kruzhka pri Leningradskom Gosudarstvennom Universitete, No. 5, pp. 28–9.

Ember A. (1930), Egypto-Semitic Studies, Verlag Asia Major, Leipzig.

Sethe K. (1902), Das aegyptische verbum im altaegyptischen, neuaegyptischen und koptischen, Leipzig.

Sethe K. (1925), Die Vokalisation des Ägyptischen, Verlag der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Leipzig.

Spartak ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DENOTATIONS OF OBELISKS

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DENOTATIONS OF OBELISKS

A. A. Spartak

PhD (History) Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts, 17, Rabkorovskaya Str., Minsk, 220008, Belarus spartakala@gmail.com

The article is devoted to the study of the ancient Egyptian denotations of obelisks. In Egyptian language, obelisks were denoted by the word txn. The etymology of this word is unknown. Apparently, the Egyptian word txn was associated with the physical characteristic of the named object (in the categories of the worldview of modern people) – with its luminosity (in the categories of the worldview of the ancient Egyptians). In different historical periods of the development of the ancient Egyptian state and depending on the stage of development of the Egyptian language, the obelisks had different designations. In the Amarna period, the ancient Egyptians used to denotation the obelisk the word bnbn. In all probability, it was associated with the religious reform of Akhenaten and an attempt to limit the influence of the Theban priesthood, distance from the Theban cult of Amun. Since obelisks were an ancient attribute of the institution of royal power, confirmation of the direct origin of the king from the sun god, Akhenaten had to use them in his ritual service. However, it was unacceptable to emphasize the connection of the obelisk with Amun, and the ancient Egyptians used the word bnbn to designate it. Since the ancient Egyptian perceived these objects as identical – as symbols of light and creation, the connection between them was obvious. Since the New Kingdom period, the hieroglyph “obelisk” has been used as a consonant component (m + n) of the words mnw (“monument”), Imn (“Amun”), jmn (“hide”). Here, according to the author, it is more correct to resort to the interpretation of such an innovation through the changed worldview categories of the Egyptians of the New Kingdom, and, accordingly, the linguistic categories. The semantic field of the word “obelisk” in this period contained the words mnw – “monument” and Imn – “Amun”, in both concepts the same hieroglyph mn was used which is a consonant component. The words formed from this hieroglyph expressed the idea of something both divine and firmly established, founded, fortified: for example, the verbal form mn – “to be strong, firm, strong, stay, be established”. The obelisk had similar properties. Therefore, the characterization of mn should be understood as a characteristic of both the monuments themselves, and those periods of the history of Ancient Egypt when the obelisks were erected – periods of the firmly established world order of Maat, prosperity, stability.

Keywords: Ancient Egypt, obelisk, institution of royal power, Egyptian language

Preislamic Near East 2021, (2):139-146

https://doi.org/10.15407/preislamic2021.02.139

Full text (PDF)

REFERENCES

A Latin Dictionary (1879), Founded on Andrews’ edition of Freund’s Latin Dictionary. Revised, enlarged, and in great part rewritten by Charlton T. Lewis, Ph.D. and Charles Short, LL.D, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Budge E. A. W. (1926), Cleopatra’s needles and other Egyptian obelisks: descriptions of all the important inscribed obelisks, with hieroglyphic texts, translations, etc., Religious Tract Soc., London.

Chabas F. J. (1868), Traduction complète des inscriptions hiéroglyphiques de l’obélisque de Louqsor, place de la Concorde à Paris, Maisonneuve, Paris.

Chabas F. J. (1872), Études sur l’antiquité historique: d’après les sources égyptiennes et les monuments réputés préhistoriques, Maisonneuve, Paris.

Gardiner A. H. (1957), Egyptian Grammar. Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, 3rd Edition, Griffith Institute & Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Kaiser W. (1956), “Zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie”, in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo, Bd. 14, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp. 104–16.

Lepsius K. R. (1849–1859), Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aephiopien, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, available at: http://edoc3.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/lepsius (accessed 29.11.2020).

Martin K. (1977), Ein Garantsymbol des Lebens. Untersuchung zu Ursprung und Geschichte der altägyptischen Obelisken bis zum Ende des Neuen Reiches, Hildesheimer Ägyptologische Beiträge, 3, XVII, Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim.

Nicholson P. and Shaw I. (eds) (2002), The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London.

Sethe K. (1910), Die altägyptischen Pyramidentexte nach den Papierabdrucken und Photographien des Berliner Museums, Bd. II: Spruch 469–714 (Pyr. 906–2217), J. C. Hinrichsche Buchhandlung, Leipzig.

Shmakov T. T. (2014), Drevneyegipetskiye teksty piramid (rabochaya versiya), available at: https://www.academia.edu/7712009 (accessed 29.11.2020). (In Russian).